Sunday, December 27, 2009

"Thoooo", Says the UK Border Agency

The snow flakes fell steady and gentle from the grey skies. The streets were devoid of the usual throng of people and cars. As I pushed on against the wind, my shoes cold and wet in the snow, I had an uneasy feeling about what lay ahead.

My client, Nazira (name changed) pushed her baby buggy along in the slush, her knuckles and hands going white from the cold. I gave her the extra pair of gloves I happened to have with me; their purple and black stripes adding a touch of the absurd to her otherwise sober dress –brown salwar kameez, a white jacket and a pale green shawl. I wondered how she managed to weather the cold in that.

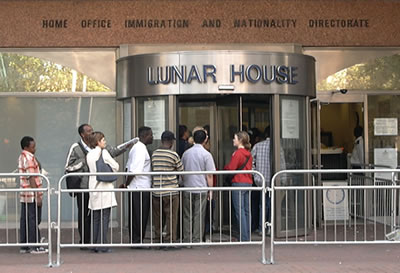

We had travelled a long way across London to get to our destination - Lunar House - home to the offices of the UK Border Agency (UKBA). It is an uninviting place at the best of times and on this dark morning it rose up like a Castle of Doom.

I had to make the journey with Nazira to the UKBA because she didn’t know how to navigate public transport in London. The plan was to accompany her into the building, as far as I was permitted and eventually leave her with an interpreter. Nazira’s mission was to claim asylum in the UK because Pakistan was no longer safe for her.

I had written a research paper in college on immigration to the UK and the honest-to-God truth is that its policies seemed designed to keep out Blacks and Asians. Lunar House, I knew, had a very dusty ‘Welcome’ mat; the word barely discernible; trampled upon by the thousands who came each day, and who it seems were often only grudgingly given entry into the UK.

So I was actually quite curious about what it would be like inside this notorious and famous building.

I knew within 20 minutes.

Asylum seekers are directed to a separate floor and Nazira was escorted up in the lift by a staff member while I was asked to take the stairs. I met her upstairs and we went through another round of security screening. The UKBA had a nice assemblage of races on display. A South Asian male officer went through our bags while a Caucasian male chatted with two women – one Black, the other Caucasian. They were discussing dry skin and how to moisturize it in the winter.

At the end of the screening, I approached their desk because Nazira doesn’t speak much English, and politely informed them that I was accompanying Nazira who wanted to make an asylum claim.

“Who are you?”, the Black woman shot back.

“I’m her case worker from a voluntary organization.”

“Do you have any identification?”

I didn’t because I hadn’t intended on staying with her. But since she asked me I showed her the only thing I had.

“I have a driver’s license.”

“Are you American?”

“No, I’m Indian.”

At this point, the White woman, who had been standing like a boarding school matron to the left of the desk, felt the need to butt in.

“Do you have a work permit?”

“Yes.”

“Hmm… strange. I wonder how that happened,” she said, being unnecessarily sarcastic.

They don’t like pesky representatives of asylum seekers because it forces them to be restrained. Not surprisingly, both women had it in for me. All veneer of professionalism was dropped and before me emerged two ordinary morons with extraordinary powers.

The Black woman said rudely, “I want you to stand back so that we can talk to her (Nazira).”

“Alright, but she needs an interpreter.”

“Yeah, we’ll have one but you go stand back. I don’t like who you are.”

I was outraged but unsure of how to respond to this verbal assault. I feared they would take it out on Nazira. But so stinging was the effect of her words that I laughed dramatically while repeating her words, saying, “You don’t like who I am? Ha!”

However, with no ID, I was forced to step back and let Nazira take over.

She was given a shitty ride. They attacked her in their fluent English without calling an interpreter while she mumbled feeble responses to them in whatever English she could muster up. They discredited her story openly and eventually told her to go wait in a queue for an interview. I don’t know what happened after that because the white male officer was dispatched to physically intimidate me into leaving the building.

Lunar House had spit me out in 20 minutes. The heat of my anger made me oblivious to the miserable cold outside. I walked back hotly to the train station to make the long journey back to the other side of town. It was as if all the adorable things about Britain – Marmite, Bobbies, double-deckers, Quality Street, Mini Coopers and afternoon teas – had all gone up in one big mushroom cloud of smoke.

One week later:

Nazira made her claim and will be called for an interview in January. My life is good and fine again and the perspective is back. They were two morons in a country of about 60 million.

Now where did I keep those chocolate Digestives?

Tuesday, December 08, 2009

Book Review: Life on the Golden Horn

Why should you read a travelogue on a journey from England to Turkey written in the early 18th century? There are, after all, plenty of resources today, some would argue too many, to get information on these places that is both current and well-researched. Yet, I can safely say that I’ve learnt more about what life was like in the Ottoman Empire through this travelogue ‘Life on the Golden Horn’ than any history book or encyclopedia could have taught me.

This slender volume is a collection of letters written by the English woman, Mary Wortley Montagu who travelled through Europe to Constantinople as the wife of a diplomat. Incredibly, she is heavily pregnant through the whole journey, but such is her curiosity about people and places that in all her letters back home there is hardly any mention of a trimester or morning sickness. Instead she drinks deep from the cup of life leaving behind a most memorable account of the attitudes of the time but more importantly giving the English-speaking world an important glimpse into the world of women in the Ottoman Empire. Her feminist perspective confirms the place of travel writing as literature, history, anthropology and even international affairs and journalism.

Mary Wortley Montague traveled through the 'war-torn Balkans' and ended up in the Turkish capital, Constantinople, from where she sent some of her most entertaining dispatches. Most accounts of the Ottoman Empire till her arrival had been written by men, with no window into the lives of women and who therefore could only make prejudiced guesses. Montagu ‘s first achievement then is to bring a gendered perspective to travel writing. She writes with a fine confidence, declaring, “Now that I am a little acquainted with their (Ottoman women) ways I cannot forbear admiring either the exemplary discretion or extreme stupidity of all the writers that have given accounts of them.”

Her most memorable accounts are the times spent with various Turkish women. She generally finds them extraordinarily beautiful, extremely warm and lavishly gracious hosts. She says, “’Tis surprising to see a young woman that is not very handsome.” When she enters a hamam for the first time, it is packed with women sprawled on the floor in various poses of indolence in a “state of nature.” But, she remarks, that contrary to the sniggering and whispering that may have accompanied the entry of a new woman into such close circles in Austria or England, here she encounters only smiles and welcoming eyes. She is even urged to undo her elaborate garments to join them in their indolence, but when the complex machinery of an 18th century English gown is revealed to them, the quest is duly abandoned.

The relevance of travel writing is further underscored by Montagu’s observations on the veil. Far from the cloak of oppression it symbolizes today, Montagu finds it a liberating “masquerade”, allowing women to go where they please, take on lovers and be free from street harassment (some things apparently don’t change).

But Montagu wouldn’t be so interesting if she didn’t also say things that would certainly end any travel writers career today. Her prejudices are all laid bare before a more politically correct 21st century reader. For instance, she declares in a sweeping generalization, that all Austrian women are generally ugly. Her offence is not restricted to Austrians. Interestingly, she says that every Turkish Pasha has a Jew who is like his homme d’affaires without whom functions of state could not be carried out. She misses the irony in her own declaration when she claims that Jews have made themselves so useful that they are guaranteed the protection of the state. Far from recognizing why they may need protection, she sees it as Jews exploiting “every small advantage.” Today she can comfortably be accused of displaying anti-Semitism.

Montagu is a product of her times, so her writing often reflects prevailing attitudes. But to her credit she also attempts to bust many of the myths surrounding the Ottoman Empire and its people. She insists they are not the barbarians of popular imagination. By way of example she points out that she sees the Turks treating their slaves in a much more humane fashion that people in England. She also says that crime in the Ottoman Empire is much lower than in, England again.

At some point during these travels, Montagu gives birth to a baby girl. But she is so taken up by the splendors of Turkey that her new daughter barely gets a mention in the letters. In her last letter from this collection she wistfully says that she envies the blissful ignorance of a milk maid who knows nothing of what lies beyond England’s shores. In fact, faced with living under England’s gloomy winter skies again, she almost wishes she forgets about Constantinople’s evening sun herself.

One of the pleasures of Montagu’s writing is the fact that it is unfettered from trying to be politically correct. Her observations are sharp, acerbic, generous, unkind, rapturous. So much of today’s travel writing pales in comparison. That’s why her 18th century account of her travels can still enlighten.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)